Sheldon College was founded in 1997 under the stewardship of Principal and CEO, Dr. Lyn Bishop, OAM. Guided by a philosophy of Love, Laughter and Learning, Dr. Bishop had a vision to open a school that would leave a legacy for children in the Redland Shire.

Located on 56 acres in a semi-rural setting, the College is committed to providing a quality education for all students in a safe, secure learning environment characterized by high standards for both staff and students in the areas of dress and appearance, behavior, individual scholarship and work habits.

Sheldon College encourages and enables students to succeed in a constantly changing world ensuring students leave equipped with the necessary skills and knowledge to become self-directed learners, effective communicators and collaborators, creative thinkers, problem solvers, innovators, information and media literate, skilled in the core literacies, and possess high self-esteem.

The challenge

The story commences with the College identifying the need to be guided by a framework and common language for ensuring quality teaching and learning. Implementing Marzano’s “Art and Science of Teaching” (2007) instructional framework, provided academic staff with research-based methodologies for providing high-quality instruction, while also taking into account the needs and abilities of individual students.

Marzano describes the art and science of teaching as a mixture of expertise in a vast array of instructional strategies, combined with the profound understanding of individual students and their needs at particular points in time.

Individual classroom teachers must determine which strategies to employ with the right students at the right time and make on-the-spot decisions about which strategies to employ. This aspect shows that a good part of effective teaching is an art. However, teachers have a toolkit of instructional strategies, and they carefully select and plan which strategy would be most effective to teach new content and skills. Therefore, there is also a science to teaching.

Teachers that work within the Marzano Instructional Framework design lessons and units of work by carefully planning and reflecting on the following design questions in their professional practice.

- What will I do to establish and communicate learning goals, track student progress, and celebrate success?

- What will I do to help students effectively interact with new knowledge?

- What will I do to help students practise and deepen their understanding of new knowledge?

- What will I do to help students generate and test hypotheses about new knowledge?

- What will I do to engage students?

- What will I do to establish or maintain classroom rules and procedures?

- What will I do to recognise and acknowledge adherence and lack of adherence to classroom rules and procedures?

- What will I do to establish and maintain effective relationships with students?

- What will I do to communicate high expectations for all students?

- What will I do to develop effective lessons organised in a cohesive unit

The College identifies continuous improvement as a key organisational value, challenging academic staff to continually refine and develop their professional knowledge and practice. The College recently embarked on developing and extending the work already undertaken in previous years around learning goals and tracking student progress.

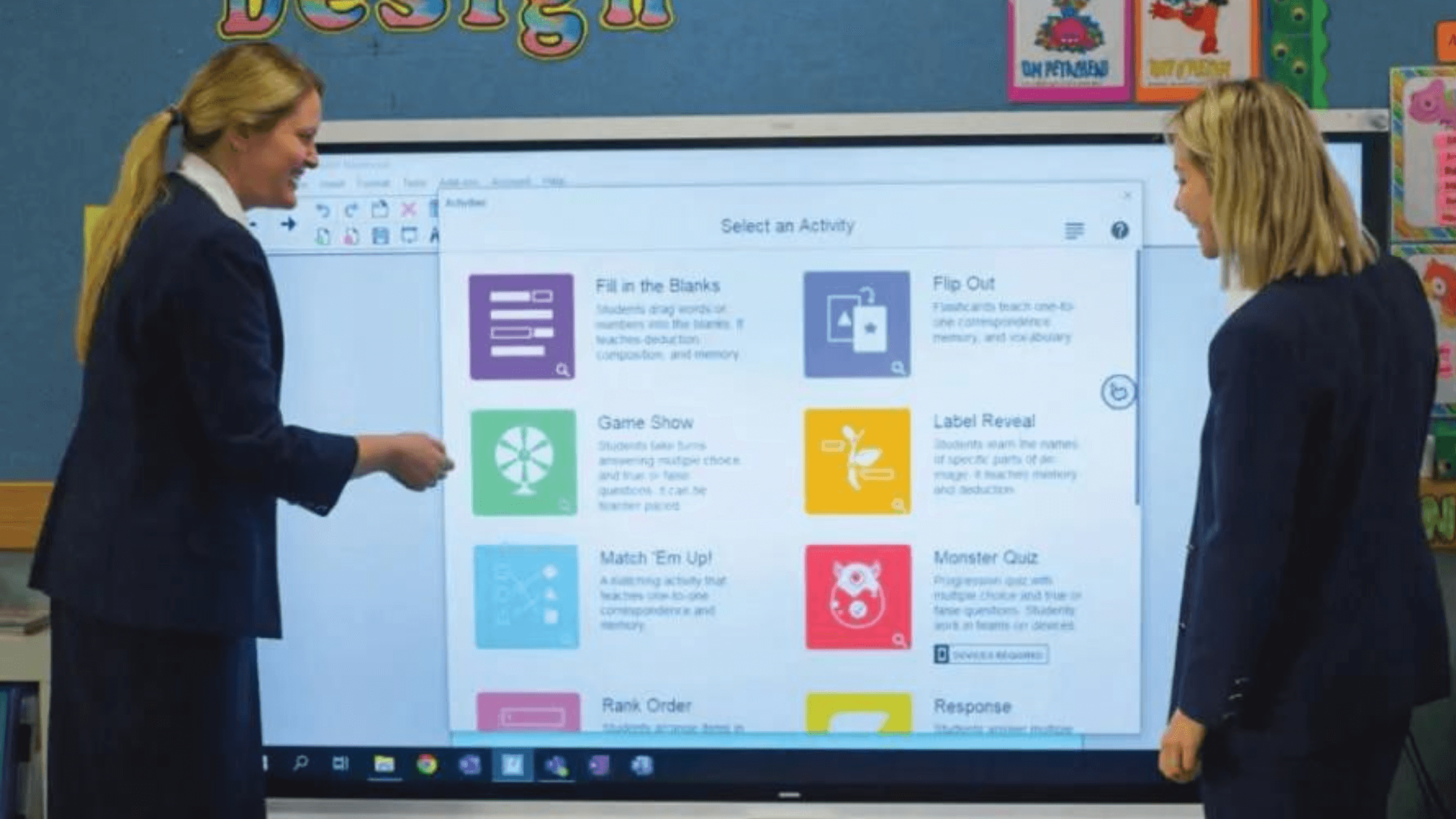

This initiative broadened teacher toolkits and instructional strategies to provide highly effective feedback as part of the learning cycle, by harnessing a range of resources and digital tools.

As a seasoned educator, Richard McLaughlin has been able to embrace technology to offer individualized instruction to meet the needs of his students. As an autistic support educator at High School of the Future in Philadelphia, he teaches students in a single classroom who have a range of abilities, Pre-K through 12.

Using the SMART Board® as a collaboration tool for he and his students, Richard has been able to enhance the way his students learn for the last 11 years in his classroom. In the morning, as students check in at the interactive display, they can choose their own pen tool color, which is more significant than it may seem, Richard says.

“I’ve taught them to change the pen color. It’s always a big deal, you know? One wants to write in purple, or yellow or black or red. It may not seem like much, but for a kid who’s at the level of a three-year-old level, for them to go up to the board, pick up the pen, change the color, find their name and trace it — that’s quite an accomplishment.”

– Richard McLaughlin

These students have the opportunity to learn to share and cooperate, as they pass the pen to the next person to find their name. “The change in these students is the ability to wait their turn, to applaud and to give feedback to the other students when they do something good,” he says. “With autism, some of these kids don’t recognize that there are other people in the world. It’s something we work on daily.”

Richard can accommodate the needs of different students with images, colors and text, presented on the board at the same time. He accesses and downloads his own PDFs from district approved curriculum and other websites to his computer to then send to the SMART Board, while also relying on lessons he finds on SMART Exchange.

When he pulls out his guitar to sing (his favorite method of teaching sight vocabulary words), he can display text on the interactive display for the students who read, but also images for the students who don’t. He has students spell out words, or point to pictures, to the tune of B-I-N-G-O.

“It’s immediately adaptable for all levels because I have very challenging words, and I have very simplistic words, and then I have kids who can just point to the picture. So, on the fly, you’ve got a student who’s at an 18-month-old level, but knows what a hammer is. He points to the hammer, I say ‘you got it!’ and everyone applauds for him.”

– Richard McLaughlin

When Richard taught his students about the routine of bowling (routine can be crucial for learners with autism) he illustrated each step on the SMART Board. His students get the experience of getting bowling shoes, throwing the ball and buying a snack from the vending machine.

Replicating the lesson, and others like it, with paper, pen and scissors would have taken hours, he says. When teaching math, Richard isolates certain parts of the equation to help his students focus using the Screen Shade tool.

Long division is a challenging concept for most learners, but being able to isolate single steps, without getting carried away, helps his students work through the problem incrementally, Richard says. “They understand it because I’m able to manipulate the math problem by covering parts of it — parts that they don’t need to be concerned with at that point,” he says, adding that his students don’t get overwhelmed by looking at what’s next.

The spotlight tool helps his students in the same way by eliminating the noise of other content on the board. More conventional teaching styles might assume students can do this on their own, Richard says.

“But transferring is so difficult for some kids. I’m able to tell kids with the spotlight that I don’t want them to worry about anything else on the board right now. Our spotlight is on this problem and this problem alone.”

– Richard McLaughlin

Above all, the SMART Board helps Richard meet his students on their own levels, not where the rest of the world thinks they should be. Learn more about SMART Displays: